- Home

- Jenny Ackland

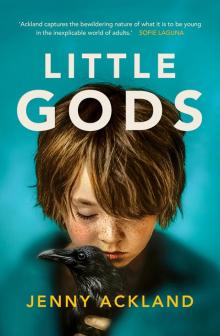

Little Gods

Little Gods Read online

Jenny Ackland is a writer and teacher from Melbourne. She has worked in offices, sold textbooks in a university bookshop, taught English overseas and worked as a proofreader and freelance editor. Her short fiction has been published in literary magazines and listed in prizes and awards. Her debut novel The Secret Son—a ‘Ned Kelly-Gallipoli mash-up’ about truth and history—was published in 2015.

Little Gods is her second novel.

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

The Secret Son

First published in 2018

Copyright © Jenny Ackland 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Every effort has been made to trace the holders of copyright material. If you have any information concerning copyright material in this book please contact the publishers at the address below.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

ISBN 978 1 76029 711 4

eISBN 978 1 76063 563 3

Internal design by Sandy Cull, gogoGingko

Set by Bookhouse, Sydney

Cover design: Sandy Cull, gogoGingko

Cover photograph: Jessica Drossin Photography

For my mother, Pamela Ackland.

CONTENTS

Prologue

BEGINNERS

THE VERANDAH PLAYS

THE PLAN

WORMWOOD

LITTLE GODS

Acknowledgements

Though she be but little, she is fierce.

William Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Act 3, Scene 2

Little Lamb, who made thee?

Dost thou know who made thee…?

William Blake, ‘The Lamb’

OLIVE MAY LOVELOCK had always felt the tree was hers. The family told stories about finding her asleep out there, a small child curled up asleep among the roots. She used to say it was the place where the orange felt strongest.

The great hulking peppercorn was a monster of branches and broad roots that pushed out of the earth like the rolling backs of porpoises and formed small caves where young children would dig and find treasure. Old shards of pinky-grey slate, white rabbit bones and, once, a bullet casing. When older, Olive took to the air to escape the anguish of the ground, climbing the tree as if it were a ladder.

Now, when she holds still and puts down her pen to bring her mind inwards, she can see there are many versions of her past self concertinaed within like a string of paper dolls. There she is six years old, then nine, then eleven. A repeating pattern of girl children, thoughts fluid yet certain. She is grown but what separates her from them? She may not sit astride a purple Dragster, toes digging deep into runners whose insides smell like wet cheese, lacing shiny plastic handlebar streamers between her fingers. She may not have bony knees or determined hair that’s too much. Eyes that sweep terrain and cloud and clear as rapidly as the sun drops beyond a country horizon. She was no longer a girl bombing off the high board but still there are snapshots of herself, images frozen in time that appear randomly, overlaid with words that could be borrowed from fairytales: beeswing, gidgee, fiddleback.

As a child, trapped in the savage act of growing up, Olive had sensed she was at the middle of something, so close to the nucleus she could almost touch it with her tongue. But, like looking at her own nose for too long, everything became blurry and she had to pull away. She’d reached for happiness as a child, not yet knowing that the memories she was concocting would become deceptive. That memories get you where they want you not the other way around.

Thoughts circle and pull at her. No matter how often she walks the city beaches, her mind finds itself back at Serpentine. A person can try, but old sorrows travel with you and perch on your shoulders like fraternal twins, and try to tell you things. You carry your past with you and along the way it repeats indigestibly, lodged like a rock in the belly, the gullet, the bowel, wherever it is a person carries their messes and shame. As the years started to pull behind her like toffee, her mind always managed to find itself at her uncle and aunt’s farm. And whenever she returned to those dark sticky years, it was still surprising how it all unravelled so quickly, the summer she turned twelve.

BEGINNERS

EVEN AT TWELVE Olive had known that others thought her family odd. Those Lovelocks, people would say, their looks loaded with meaning. They said it in the butcher, the supermarket and the haberdashery. They said it at the milk bar and in the playground at school.

‘They say her wedding dress was made of wool,’ one woman said to another in the newsagent.

‘And there’s the haughty one.’

‘And that Thistle.’

Silence then, and knowing nods, as Olive watched from behind the newspaper rack with a lemon-lime Chupa Chup in one hand and thirty cents in the other.

Her mother was one of the Nash sisters, a clutch of prickly women who’d grown up in Stratford. Three girls maturing behind a high hedge with neighbours on both sides who strained at fences and peeked through holes. Their mother, sensing all those opened ears, made sure transgressions were dealt with inside the house, windows and doors shut tight. As if that weren’t enough, there were the Lovelock brothers, in sheep not wheat. The way people said it made it sound like a mistake.

When the two families had merged matrimonially, things had become complicated and not just for the leftover sister. It was a truth Olive Lovelock also struggled with as she stood in front of her grade six class on a Friday afternoon early in December.

In her hands was her family tree chart and she was trying to explain how the people fitted together. She told the class her mother was called Audra and was a housewife and shy, and that her father was Bruce and worked in some unclear way for the Wool Board. She told them that sometimes her dad talked about ‘fribs’ and ‘wefts’ and that he had a wall of shelving in the shed at home where he poked grading samples from different breeds.

The other children sat on the carpet with their simple drawings on their laps. Linear, vertical, neat. Olive squinted at her hand-drawn diagram. All the lines were crisscrossed with wild loops and arrows that flared in the direction of explanation keys she’d put in boxes down the bottom. Some of the children were looking at her, some at the ground. Bosco Scully was in the first row and punched the arm of the boy next to him. The teacher was sitting at the back, at one of the student desks. Her eyes were closed.

Olive knew she didn’t have much time so was racing to finish, but Mrs Barton interrupted her and placed a fingertip to the side of her head.

‘Time to finish up,’ she said. Olive nodded, but it was hard. She had more to say. She was excited because as well as the family tree presentations it was the day of her twelfth birthday. She’d brought a chocolate cake for lunch to share with the other children—not that any of them deserved it. She and her father had made it after dinner the night befor

e, trying to keep quiet in the kitchen. The cricket had been on the radio with the volume down low. They’d stood side by side in front of the cooling rack and agreed they’d done a pretty good job. Then her guts had twisted as the cake sank in the middle.

‘Oh.’

‘Don’t worry, big girl. We’ll just build it up a bit.’ Bruce pointed at the centre. ‘With extra icing, here and here.’

But Olive had put too much food colouring in the icing and it had turned blood red. It dripped down the sides and collected in a viscous puddle in the concave centre and it had been this evil confection that made Bosco Scully spew. The emphatic red hurl had landed on the carpet right in front of Mrs Barton’s shoes, making her drop the metre ruler. After the vomit had been cleaned up, standing in front of the class to do her talk, all Olive could be certain of was that two sisters had married two brothers with one of the sisters and one brother left over.

‘It’s a bit tricky,’ she said. ‘You see—’

‘That’s fine, Olivia,’ Mrs Barton said. ‘You can sit down now.’

But Olive planned to tell the class how her uncles said ‘flock’ for the very rude word and that birthday cards in her family were always written ‘Happy Birthday to Ewe’. She was going to show that bit on the board because otherwise they wouldn’t get it. Also, she was going to tell them that her aunt’s wedding dress was made of silk, not wool, like some people had said. But mostly, she wanted to remind Mrs Barton that her name was Olive.

She went and sat down. The children on either side lifted their knees and it was Snooky Sands who made the most fuss about shifting backwards to make room.

Olive had asked Snooky only once why she was being so mean.

‘My mum said not to play with you. It’s because you’re a bad influence.’

Olive watched Snooky walk away feeling the distance grow as if a real thing. She began wearing her grandfather’s old binoculars around her neck.

‘For seeing birds better,’ she told the adults.

‘For spying on people,’ she told Peter.

She’d found the binoculars in the shed at the farm and her aunt had told her she supposed she could have them. Rue always said ‘supposed’ in a way which meant she preferred Olive didn’t, but she took them all the same. She liked the feel of the strap around her neck, the weight of the glasses as they bumped against her tummy. They gave her power to know whether a person was smiling or serious, to see how their mouth stretched as they talked. If she wanted to, she could count how many times a person blinked in sixty seconds, and whether they chewed their lip while thinking about what to say next. She looked at birds with the binoculars and she looked at clouds. The binoculars made her feel she could see anything in the world that she wanted to.

SHE HEADED HOME, scraping her runners on the footpath. She stopped for a while at Miss Alexander’s gate to try to get the orange cat to come for a pat, but it rolled on the driveway and ignored her. She called to it, keeping an eye out because the old lady was crazy. She had long grey hair that fell out of her bun, bushy eyebrows and no front teeth. She hissed like a goose at children if she ever caught them at the front of her house. Once she had scared Olive as she walked home from school and had pushed her up against the hedge asking her what her name was. Olive scratched the backs of her legs trying to get away. She waited a bit longer at the end of the driveway watching the cat.

She wanted a cat or a dog, she didn’t mind which, but her mother had said no.

‘What do you want to have pets for?’ her mother had said. ‘They just die, and then you get sad.’

She was almost at her house when she saw Peter waiting for her. On the footpath she stood in front of him and swung her binoculars to her eyes.

‘Where were you?’ she asked him. She rotated her body in small increments. ‘Bosco threw up.’

‘The high school? My mum wanted to go and talk to the principal.’

‘What even for?’

‘Who even knows. I think she wanted to look again. I don’t know, she doesn’t tell me why.’ He made a noise that sounded like chuh in the back of his throat.

‘But there’s only one high school around here and we did the visit already.’

‘I know.’

‘Maybe she’ll send you to boarding school.’

‘As if.’ He shook his head back to get his hair out of his eyes.

Like Olive, Peter Stonehouse was an only child and from the beginning he had adhered to her with commitment even though she always picked her scabs and sometimes her nose. He liked how pointy her chin was and didn’t care that she could be ferocious in her extremes of emotion. To stand by and watch her cool interactions with others—even adults—was thrilling for a boy like Peter. He was someone who listened to the grown-ups and did what they told him. He’d realised the adult way was not a choice but a rule until you were a grown-up yourself and got your own turn. But Olive May Lovelock, she was taking her turn now. The only thing he didn’t really like about her was how she could be opposite sometimes. He couldn’t remember the word but it started with ‘h’. It meant that she didn’t always do or say things the same way all the time. She was always changing her mind. He thought the ‘h’ word also described someone who was always sick and complained about it like his aunty Mol but he wasn’t sure.

‘Why did he spew?’

‘Probably the cake. It was really red.’

‘I’m going to the pool. Coming?’

‘I can’t. We’re going to the farm for the weekend, for my birthday.’

‘You can come for a while, it’s only—’ he raised his wrist and looked at the watch that had been his grandfather’s ‘—quarter to.’ He gave the watch a dry kiss.

‘You’re going to marry that watch.’ Olive lifted her binoculars in the direction of the lady across the road who lived with another lady who wasn’t in her family. The story was that one of them had fed her husband glass and gone to prison. No one knew which of the two women it was.

‘I told you, it’s been near Germans,’ Peter said.

It looked like just an ordinary watch to her. The face was round and had a heavy brown leather band. The inscription on the back read PDS 26 May 1935—Peter had the same initials as his pop, Phillip—and his grandparents’ wedding date. Peter had made the mistake of telling Olive that he put the watch to bed each night in a square box with cotton wool.

‘You can come for a quick swim. I’ve got snakes.’ He touched his pocket.

‘I don’t have my bike or my things.’

‘So get them.’ Peter started riding slowly beside her as she walked. ‘I’ve got mine already.’

They stopped by her place then set off again. Peter was talking about the new high school uniform and the booklist but she wasn’t listening, she didn’t care about any of that. She was thinking about whether she had any coins in her pocket. If she did, she thought she might get a Razz or a Glug, maybe both. She rode down the footpath with Peter behind her. Overhead there was a thin line of white cloud that hung above them, hard-edged against the pale blue sky. Perhaps it was a trail from a plane but Olive didn’t think so. It looked more like a cloud that didn’t realise what shape it was meant to be. They turned left at the end of the road and continued on to the Stratford Memorial Pool.

HEAT RADIATED OFF the black pitch in the car park and they pushed through the turnstile, the noise of shouts carrying across the space. The pool complex was filled with children and adults, some lying on towels on the cement, others on the grassed slopes which rose in waves around the perimeter. Olive looked at the small kiosk with the big clock over it. Four o’clock. She had an hour or a bit more.

They got into their bathers in the change rooms that smelled funny and walked across the grass to find a spot where they dumped their things and walk-ran to the fifty-metre pool, increasing speed once they hit the hot cement. They jumped in from the edge—Peter with his legs tucked into a sitting bomb and Olive in a silent-scream safety jump—and began to cycle throug

h their usual activities. Handstands down the shallow end. Getting on each other’s shoulders in turn. Swimming underwater and making it two-thirds of the way across.

Once, when getting out and running along to the shallower end, Olive knocked over a small child. The girl sat on the concrete, howling, saliva swinging from her open mouth. Olive bent over and tried to pick her up but the girl just sat and cried. Then the mother was there.

‘I didn’t mean to,’ Olive said. ‘It was an accident.’

‘It’s fine, don’t worry,’ the mother said, smiling. Olive looked at the little girl who had stopped crying and was getting up. Olive straightened and walked to where Peter was waiting and jumped back into the water.

‘What happened?’ he said.

‘Nothing. It wasn’t my fault.’

She and Peter sat a while on the bottom with their arms crossed, shouting messages to each other, and then climbed out and lay on their towels to eat sherbets and suck Razz tetra-paks.

‘Gary Sands,’ Peter said.

Olive sat up and shaded her eyes. Gary Sands was standing in waist-deep water with his mates. He was holding someone under the water and laughing. An older girl, Liz, struggled to the surface and broke free. Gary lurched back, head snapping, and whinnied like a horse.

‘He’s mental,’ said Olive.

‘Takes special medicine my mum said.’

‘Yeah. Mental-case medicine.’

She picked up her towel. ‘I have to go.’

‘Let’s do the boards, just quickly? Only a few times, like ten?’

‘Alright.’ She didn’t really need to go. Her father wouldn’t be home yet and her mother would be still lying down.

The diving pool was a place where you spoke in a whisper, like at church. Older boys flung themselves off the platform with frenetic, back-arching horseys and plummeted from the high boards, their thumping bombs pushing spray high into the air. The teenage girls gathered in hard-hipped broods nearby, standing with one leg straight and the other bent. Olive didn’t know why they stood like that but they did. They were the girls who had pierced ears, sleepers which they rolled in their lobes as they watched the boys. If they ever went in the water, they kept their heads out so that their fringes stayed flicky and Olive didn’t understand that either. What was the point of going to the pool if you didn’t even go in, and if you went in, to not go under all the way?

Little Gods

Little Gods